The Art and Science of Remembering

Key techniques for creating a

lasting memory

기억력을 높이는 기술

Robert

Roy Britt / Jul 2

Cramming

for the exam, repeating someone’s name: Some experts say they’re not that

effective at solidifying a memory.

Memories

don’t just happen — they’re made. In the brain, the process

involves converting working memory — things we’ve just learned — into long-term

memories. Scientists have known for years that the noise of everyday life can

interfere with the process of encoding information in the mind for later

retrieval. Emerging evidence even suggests that forgetting isn’t a

failure of memory, but rather the mind’s way of clearing clutter to

focus on what’s important.

Other

research shows the process of imprinting memories is circular, not linear.

“Every time a memory is retrieved, that memory becomes more accessible in the

future,” says Purdue

University psychologist Jeffrey Karpicke, who adds that only in recent years

has it become clear just how vital repeated retrieval is to forming solid

memories. This helps explain why people can remember an event from childhood —

especially one they’ve retold many times — but can’t remember the name of

someone they met yesterday.

Making

memories stick

기억이 오래 유지되도록

하는 법

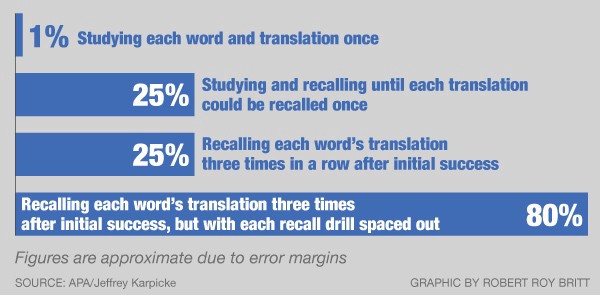

Karpicke

and colleagues have shown that practicing retrieval, such as taking multiple

quizzes, is far superior in creating solid memories than doing rote

memorization. To study this, they had students use different methods to learn

the translations of foreign words flashed on a computer screen:

·

One group simply studied

each word and translation once, with no quizzes.

·

A second group was

quizzed until they could recall each translation.

·

A third group was

quizzed until they could recall each translation three times in a row after

initial success.

·

The fourth group did the

same as the third, but their quizzes were spaced out in time.

A week

later, all the students were quizzed again. Here’s the amount they remembered

via each method:

Based on these findings, Karpicke says self-quizzing — with flashcards or other means — can

be an effective way to solidify new knowledge into memories, but the best way

is to space those quizzes out, rather than doing them all in one sitting.

암기 카드 등을 통한 ‘스스로에게 질문하기’는 새로 학습된 정보를 기억으로 굳어지게 하는 데에 효과적이다. 한

번에 모든 질문을 하는 것보다는 시간 간격을 두고 질문을 하는 것이 더 효과적이다.

For more

complicated memory tasks, such as memorizing a long speech, some long-used

strategies do appear to hold up today. The ancient Greeks had an elaborate

method to remember complex trains of thought. They called it the “Memory Palace(기억의 궁전),” also

known as the method of loci. It works because research

suggests people are much better at remembering things they can see, rather than

raw facts or abstract concepts.

The way

to create a Memory Palace is to walk through a familiar place (like your home)

and make offbeat associations between the objects you know well and the things

you wish to remember. Let’s say you’re giving a talk about global warming. If

you were to use the Memory Palace technique to remember your lines, you might

take a walk through your home and associate the fridge with an unusually frigid

winter storm. You would then pretend SpongeBob is right there, in your kitchen,

eating a Krabby Patty, to represent global warming’s negative effects on sea

level and the health of crustaceans. During your talk, you take a mental stroll

through your kitchen and let the wacky associations bubble up.

Modern

memory competitions, in which participants memorize entire poems or the order

of several shuffled card decks, have resurrected the Memory Palace technique.

Ben Pridmore, a three-time World Memory Champion, used the practice to memorize

the order of 1,528 random digits in one hour, among other feats of mental

gymnastics.

Joshua

Foer, a science journalist, covered the United States Memory Championship in

2005. Foer figured he’d be better prepared to write about the mind-boggling

contestants if he learned a little about their techniques. He spent a year

studying the tactics. In a 2012 TED Talk, Foer explains

how memorization is all about associating the mundane with the interesting or

even the bizarre:

“As bad

as we are at remembering names and phone numbers and word-for-word

instructions… we have really exceptional visual and spatial memories,” Foer

says. “The crazier, weirder, more bizarre, funnier, raunchier, stinkier the

image is, the more unforgettable it’s likely to be.”

Foer got

pretty good at memorizing. Instead of covering the competition the following

year, he entered it. “The problem was, the experiment went haywire,” he says.

“I won the contest. Which really wasn’t supposed to happen.”

“Great memories are learned. But if you want to live a

memorable life, you have to be the kind of person who remembers to remember.”

“좋은 기억에는 학습이 필요하다. 그러나 당신이 기억에 남을 만한 인생을 살고 싶다면, 당신은 ‘기억할 것을 기억하는’ 사람이 되어야 할 것이다.”

In his

bestselling book Moonwalking with Einstein, Foer says all memory

champions like himself will claim that they actually have average memories. And

science backs that claim. Back in 2002, researchers scanned the brains of World

Memory Champions while they were memorizing facts and detailed images. The results showed that

“superior memory was not driven by exceptional intellectual ability or

structural brain differences,” the authors wrote. “Rather, we found that

superior memorizers used a spatial learning strategy, engaging brain regions

such as the hippocampus that are critical for memory and for spatial memory in

particular.”

It’s not

that memory champions are smarter than everyone else. They just work hard at

remembering, and therefore apply more of their brains to the task.

A couple

easier techniques

기억력을 높이는

간단한 기술들

If

creating a Memory Palace seems too involved or absurd, there are simpler

strategies you can try, like taking a nap or doing nothing at all for a period

of time.

Studies

have shown that sleep is important for memory formation, and several studies have

indicated that naps function just like overnight sleep. In one study published

in the journal Sleep earlier this year, researchers had 84

college students learn some basic facts. One group then napped for an hour,

another group just took a break and watched a movie unrelated to the material

they’d learned, and the third group crammed, going back over all the material.

“When

retention was tested immediately after learning, both napping and cramming

produced better retention than taking a break, but only the nap benefit

remained significant when tested one week later,” the researchers concluded.

Michael

Craig and Michaela Dewar at Heriot-Watt University in the UK have found in

several studies that sitting quietly and doing nothing — what they call “awake

quiescence” — helps people remember more. The idea is that when you learn

something new, what you do next is crucial in helping you retain that

information, and taking a pause might be the best choice to let the brain

process new information.

In a

2012 study led by Dewar, people ages 61 to 87 heard two short stories and were

quizzed on the details of the stories immediately after. Then the people were

split up into two groups. For 10 minutes, half the people in the study played a

computer game that required some thought, while the others sat in a quiet, dark

room, alone, with their eyes closed. Neither group was given any instructions

about trying to remember things (they were told the researchers were headed off

to prepare for the next test).

The quiz

was then repeated a half-hour later and again a week later, and in both

retests, the people who sat and did nothing for 10 minutes “remembered much

more,” the researchers reported in

the journal Psychological Science.

“Our

findings support the view that the formation of new memories is not completed

within seconds,” says Dewar. “Indeed our

work demonstrates that activities that we are engaged in for the first few

minutes after learning new information really affect how well we remember this

information after a week.”

“새로운 정보를

학습한 직후의 시간을 어떻게 사용하는지가 일주일 후 해당 정보를 얼마나 잘 기억할 수 있을지를 결정한다.”

The

biological mechanisms behind awake quiescence haven’t been investigated. But

Craig says he thinks that memories are fragile and vulnerable to disruption and

that hanging onto them requires sleep or quietude to allow them to consolide,

or solidify.

“Findings in rodents and humans indicate that the brain

consolidates new memories by ‘replaying’ them” in the minutes after initial

learning,” he says.

“우리의 뇌는

최초의 학습 이후 몇분간 기억을 ‘되감기’함으로써 기억을

더 견고하게 한다.”

“We believe that awake quiescence might be so beneficial

to memory because it is conducive to the ‘replay’ of new memories in the

brain.”

“깨어있지만

활동하지 않는 ‘침묵의 시간’은 뇌의 무의식적 ‘되감기’ 활동을 촉진함으로써 기억력에 큰 도움이 된다.”

The

replay is not conscious — it’s an automatic biological process, Craig explains.

After the memory tests, his team asks people what they were thinking about

during their quiescence period. Normally they say their minds were wandering,

as happens with anyone not engaged in a task. “People rarely report thinking

about the studied materials during these periods,” he says.

Among

the most exciting aspects of awake quiescence is that it seems to work for

almost anyone. The researchers use the same tests on the young and old, and

even people with serious memory problems. Awake quiescence hasn’t been tested

on associating names with faces, but it has been found to boost

spatial-associative memory, such as binding a landmark to a location.

“So, it is possible that quietly resting for a moment

after meeting someone new could well help you to remember a person’s name and

face better,” Craig says.

“새로운 사람을

만난 후 조용히 휴식하는 것만으로도 그의 이름과 얼굴을 더 잘 기억할 수 있다.”

The ultimate

takeaway is that improvements in recall may require the adoption of a process,

even if it’s a conscious effort to spend some time not doing much thinking at

all.

“Great

memories are learned,” Foer says. “But if you want to live a memorable life,

you have to be the kind of person who remembers to remember.”